domingo, agosto 04, 2013

sexta-feira, agosto 02, 2013

Pitagórica, 24-28 Julho, N=507, Tel.

PS: 34,6% (+0.7)

PSD: 24,1% (+0.4)

CDU: 13,1% (-0.1)

BE: 8,7% (-0.2)

CDS-PP: 8,1% (-1)

Aqui. E também isto:

PSD: 24,1% (+0.4)

CDU: 13,1% (-0.1)

BE: 8,7% (-0.2)

CDS-PP: 8,1% (-1)

Aqui. E também isto:

quinta-feira, agosto 01, 2013

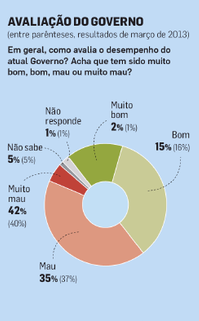

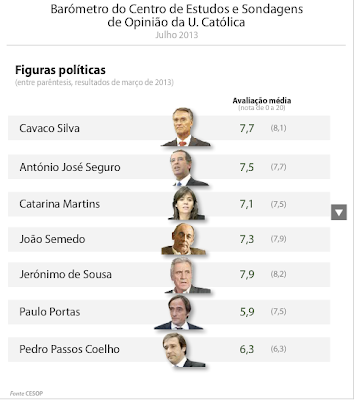

CESOP/Católica, 27-29 julho, N=1096, Face a face

Entre parêntesis, resultados de Março passado:

PS: 35% (+4)

PSD: 32% (+4)

CDU: 11% (-1)

BE: 7% (-1)

CDS-PP: 3% (-2)

OBN: 12% (-4)

Aqui.

PS: 35% (+4)

PSD: 32% (+4)

CDU: 11% (-1)

BE: 7% (-1)

CDS-PP: 3% (-2)

OBN: 12% (-4)

Aqui.

segunda-feira, julho 29, 2013

Crisis and party system change: Greece, Portugal, and others

Alexandre Afonso makes interesting points about how and why the financial crisis and austerity policies hit the Greek party system more severely than the Portuguese one (here, in Spanish and here, in English). A summary, hoping to do it justice:

1. First, according to Afonso, Greek parties relied more on state-sponsored clientelism and patronage than the Portuguese ones. Economic crisis and austerity thus hurt the Greek parties more severely in terms of their ability to sustain mass support.

2. Second, PASOK ruled alone in 2009 and thus could not avoid being held responsible and massively punished for the economy and economic policies. In contrast, the Portuguese Socialists were a minority government since 2009, implemented austerity policies negotiated with the PSD even before the bailout, and this made “responsibility more difficult to attribute,” thus mitigating incumbent losses.

3. Finally, according to Afonso, “technocratic governments” and “grand coalitions”, creating “a political cartel where participants make a commitment to avoid blaming each other in order to minimize electoral costs” (…)”may be the only one available for parties to survive in the current situation”.

My feeling is that the first point sounds about right, the second only partially so, and the third not at all, at least to me.

I’m ready to accept that Greek parties relied more extensively on patronage to muster support, and thus that it is plausible that the crisis and the austerity policies forced by the EU/IMF bailout had bigger consequences in Greece than in Portugal from that point of view. I also agree (I have made that point myself on the basis of a post-election survey) that, in the Portuguese 2011 elections, voters’ propensity to assign blame not only to the incumbent Socialists but also to a variety of other forces and factors (although not so much to the opposition parties) seems to have mitigated the punishment exacted upon the PS for the economic situation then faced and for the very need for a bailout.

However, from the point of view of Afonso’s arguments, it sometimes seems that the debacle of the Greek party system was basically something very bad that happened to the incumbent PASOK. But that’s not exactly right, is it? “Very bad” things have also happened to other incumbents in financially troubled European countries, including to Fianna Fáil in Ireland, to the Independence Party in Iceland, or even, for that matter, to the Socialists in Portugal (with a cumulative loss of 17 percentage points from 2005 to 2011). What makes the Greek crisis different from said countries was the overall massive level of electoral volatility, including the fact that the major party of the opposition (New Democracy) was also punished in 2012, even in comparison with its 2009 loss (as Afonso shows in his own graph), as well as the dramatic rise of other parties that were either new or previously much less relevant. Nothing like that happened in the 2009 elections in Iceland, in theJanuary February 2011 elections in Ireland, or in the June 2011 elections in Portugal, where the existing major alternatives to incumbents did predictably well. In fact, an even longer view shows us that the defeats suffered by the incumbents in those elections did not prevent their later (at least partial) electoral recovery since then, as the performance of the Independence Party in the 2013 Iceland elections (or of Fianna Fáil and the Portuguese PS in the opinion polls today) show.

So, if we want to treat party system “resilience” or ”change” as the thing we want to explain, what are the two cases among the ”financial crisis” countries where party systems were more badly shaken? Interestingly, and, I think, countering Afonso’s argument, these are precisely the two cases where ”technocratic” or “national unity” governments were formed. In Greece, it is fascinating to see how the performance of ND in the polls plummeted in the aftermath of the formation of the Papademos cabinet in November 2011. In Italy, one and a half years of Monti (as well as Berlusconi’s tactical withdrawal of support by the end of the term) ended up leaving the Democratic Party awkwardly associated with austerity and crisis, something that, in other circumstances, an opposition party would probably be able to avoid (if not capitalize from). The result, in both countries, is that the punishment of incumbents was not accompanied by a reward for the main challengers in the party system. Instead, protest voting appeared with enormous strength and new parties emerged or strengthened, a result, I would argue, of the shared responsibility of the major traditional parties for increasingly detested policies and their consequences.

So to me, the question is: why have the Greek and Italian party systems been so transformed, while the Portuguese, Irish, and Icelandic ones were less so? The answer, I think, may be the opposite to the one provided by Afonso: cases of “national unity”/”technocratic” governments were followed by the deeper manifestations of party system transformation. In contrast, where party government prevailed, punishments for incumbents may have been very large in some cases and smaller in others, but party systems seem (so far) to have basically preserved most of their main features.

P.S.- I cautiously avoided Spain where, in the absence of any sort of “national unity” or “technocratic” cabinets, there’s an argument to be made about an important change away from a basic two-party system and towards a more fragmented one. However, this is mostly based on polling data, and I would reserve judgment on this until an actual election takes place…

1. First, according to Afonso, Greek parties relied more on state-sponsored clientelism and patronage than the Portuguese ones. Economic crisis and austerity thus hurt the Greek parties more severely in terms of their ability to sustain mass support.

2. Second, PASOK ruled alone in 2009 and thus could not avoid being held responsible and massively punished for the economy and economic policies. In contrast, the Portuguese Socialists were a minority government since 2009, implemented austerity policies negotiated with the PSD even before the bailout, and this made “responsibility more difficult to attribute,” thus mitigating incumbent losses.

3. Finally, according to Afonso, “technocratic governments” and “grand coalitions”, creating “a political cartel where participants make a commitment to avoid blaming each other in order to minimize electoral costs” (…)”may be the only one available for parties to survive in the current situation”.

My feeling is that the first point sounds about right, the second only partially so, and the third not at all, at least to me.

I’m ready to accept that Greek parties relied more extensively on patronage to muster support, and thus that it is plausible that the crisis and the austerity policies forced by the EU/IMF bailout had bigger consequences in Greece than in Portugal from that point of view. I also agree (I have made that point myself on the basis of a post-election survey) that, in the Portuguese 2011 elections, voters’ propensity to assign blame not only to the incumbent Socialists but also to a variety of other forces and factors (although not so much to the opposition parties) seems to have mitigated the punishment exacted upon the PS for the economic situation then faced and for the very need for a bailout.

However, from the point of view of Afonso’s arguments, it sometimes seems that the debacle of the Greek party system was basically something very bad that happened to the incumbent PASOK. But that’s not exactly right, is it? “Very bad” things have also happened to other incumbents in financially troubled European countries, including to Fianna Fáil in Ireland, to the Independence Party in Iceland, or even, for that matter, to the Socialists in Portugal (with a cumulative loss of 17 percentage points from 2005 to 2011). What makes the Greek crisis different from said countries was the overall massive level of electoral volatility, including the fact that the major party of the opposition (New Democracy) was also punished in 2012, even in comparison with its 2009 loss (as Afonso shows in his own graph), as well as the dramatic rise of other parties that were either new or previously much less relevant. Nothing like that happened in the 2009 elections in Iceland, in the

So, if we want to treat party system “resilience” or ”change” as the thing we want to explain, what are the two cases among the ”financial crisis” countries where party systems were more badly shaken? Interestingly, and, I think, countering Afonso’s argument, these are precisely the two cases where ”technocratic” or “national unity” governments were formed. In Greece, it is fascinating to see how the performance of ND in the polls plummeted in the aftermath of the formation of the Papademos cabinet in November 2011. In Italy, one and a half years of Monti (as well as Berlusconi’s tactical withdrawal of support by the end of the term) ended up leaving the Democratic Party awkwardly associated with austerity and crisis, something that, in other circumstances, an opposition party would probably be able to avoid (if not capitalize from). The result, in both countries, is that the punishment of incumbents was not accompanied by a reward for the main challengers in the party system. Instead, protest voting appeared with enormous strength and new parties emerged or strengthened, a result, I would argue, of the shared responsibility of the major traditional parties for increasingly detested policies and their consequences.

So to me, the question is: why have the Greek and Italian party systems been so transformed, while the Portuguese, Irish, and Icelandic ones were less so? The answer, I think, may be the opposite to the one provided by Afonso: cases of “national unity”/”technocratic” governments were followed by the deeper manifestations of party system transformation. In contrast, where party government prevailed, punishments for incumbents may have been very large in some cases and smaller in others, but party systems seem (so far) to have basically preserved most of their main features.

P.S.- I cautiously avoided Spain where, in the absence of any sort of “national unity” or “technocratic” cabinets, there’s an argument to be made about an important change away from a basic two-party system and towards a more fragmented one. However, this is mostly based on polling data, and I would reserve judgment on this until an actual election takes place…

terça-feira, julho 16, 2013

Uma frincha

Vou fazer agora uma coisa para a qual não tenho jeito nenhum: aquilo a que se costuma chamar "análise política". O meu negócio é outro, mas perdoem a incursão em terreno alheio. É porque há uma passagem muito curiosa num artigo de Leonete Botelho e Sofia Rodrigues no Público de hoje que não resisto comentar:

Para além de eu ser distraído e ignorante, há também a possibilidade destes "pedidos" feitos há muito terem sido privados, ou até, que sei eu, de estarmos perante uma oportuna reconstrução da história política recente. Mas isso agora não interessa muito. O interessante é que de repente vejo, não uma "janela de oportunidade", mas pelo menos uma pequenina frincha por onde pode passar um acordo entre os três partidos. O PS consensualiza objectivos de ajustamento mais modestos com o Governo, os nossos credores aceitam a coisa e continuam a mandar os cheques, Seguro reclama para si o mérito de "fazer ver" à maioria os seus erros passados e o PSD e o CDS evitam eleições antecipadas potencialmente catastróficas (especialmente para o segundo, se as indicações desta sondagem se confirmarem).

Contudo, a frincha continua a ser muito estreita. Se esses objectivos consensualizados incluírem "concordar com despedimentos, cortes nas pensões", a coesão interna no PS deverá estar em risco, se José Sócrates servir de barómetro para esse efeito (e provavelmente serve). E mesmo sem contar com isso, para o PS, a equação eleitoral não é inequivocamente favorável a qualquer espécie de acordo com os partidos de governo: CDU e BE espreitam, e um ano (até menos que isso) de "salvação nacional" é muito, muito tempo. Mas a frincha está lá.

Desde há muito que a maioria e o Governo pediam um entendimento com o PS que tinha por objectivo fazer pressão à troika para ganhar vantagens nas negociações. Com isso, a maioria apresentava como argumento perante a troika um apoio reforçado no Parlamento, mas também ganhava margem para negociar matérias, como a flexibilização do défice, a coberto do PS, com o argumento de que os socialistas eram menos receptivos a medidas que implicam cortes na despesa social.Só comprovo a minha distracção e a minha ignorância, mas confesso que não sabia nada disto. Eu sabia, por exemplo, que o Primeiro-Ministro não excluía a possibilidade de flexibilizar a meta do défice para 2014, "mas faremos tudo o que está ao nosso alcance para cumprir as metas que foram agora acordadas no sétimo exame regular", e até já tem "prontos os diplomas que terminam os cortes de 4,3 mil milhões de euros que foram acordados para 2014". Sabia também que o CDS considerava que "factores externos" faziam com que fosse "prudente" admitir a possibilidade de nova flexibilização das metas do défice para 2014, mas pouco mais para além de dezenas de notícias injectadas nos jornais sobre nunca claramente assumidas posições do partido e do seu líder sobre o programa de ajustamento. O que eu não sabia era que o Governo, por considerar essas metas impossíveis (ou até, quem sabe, indesejáveis), andava há muito a pedir um entendimento com o PS para, usando o PS como "desculpa" ou para mostrar base de apoio doméstico, ganhar poder negocial frente à troika para renegociar as metas acordadas.

Para além de eu ser distraído e ignorante, há também a possibilidade destes "pedidos" feitos há muito terem sido privados, ou até, que sei eu, de estarmos perante uma oportuna reconstrução da história política recente. Mas isso agora não interessa muito. O interessante é que de repente vejo, não uma "janela de oportunidade", mas pelo menos uma pequenina frincha por onde pode passar um acordo entre os três partidos. O PS consensualiza objectivos de ajustamento mais modestos com o Governo, os nossos credores aceitam a coisa e continuam a mandar os cheques, Seguro reclama para si o mérito de "fazer ver" à maioria os seus erros passados e o PSD e o CDS evitam eleições antecipadas potencialmente catastróficas (especialmente para o segundo, se as indicações desta sondagem se confirmarem).

Contudo, a frincha continua a ser muito estreita. Se esses objectivos consensualizados incluírem "concordar com despedimentos, cortes nas pensões", a coesão interna no PS deverá estar em risco, se José Sócrates servir de barómetro para esse efeito (e provavelmente serve). E mesmo sem contar com isso, para o PS, a equação eleitoral não é inequivocamente favorável a qualquer espécie de acordo com os partidos de governo: CDU e BE espreitam, e um ano (até menos que isso) de "salvação nacional" é muito, muito tempo. Mas a frincha está lá.

segunda-feira, julho 15, 2013

Mais sobre a sondagem Aximage

A Aximage pede aos inquiridos que avaliem os principais líderes políticos como tendo actuado "bem", "mal" ou "assim-assim". Depois atribui valores de 3, -3, e 1 a cada uma das opções (-1 sem opinião). Depois agrega e converte numa numa escala de 0 a 20. É um pouco complicado (porventura excessivamente complicado), mas a regra é explicada e consistente, e logo a comparabilidade é possível. Eis a evolução:

O tombo do líder do CDS-PP é grande. Em consistência com os resultados de intenção de voto do PSD na mesma sondagem, Passos Coelho sobe. Para já, a indicação é esta: o conjunto de episódios em torno da demissão de Portas penalizou-o fundamentalmente a ele e ao seu partido, mas não o seu parceiro de coligação. Mas são indicações a confirmar (ou não) com mais sondagens que sejam realizadas após a crise da coligação.

O tombo do líder do CDS-PP é grande. Em consistência com os resultados de intenção de voto do PSD na mesma sondagem, Passos Coelho sobe. Para já, a indicação é esta: o conjunto de episódios em torno da demissão de Portas penalizou-o fundamentalmente a ele e ao seu partido, mas não o seu parceiro de coligação. Mas são indicações a confirmar (ou não) com mais sondagens que sejam realizadas após a crise da coligação.

domingo, julho 14, 2013

Subscrever:

Mensagens (Atom)